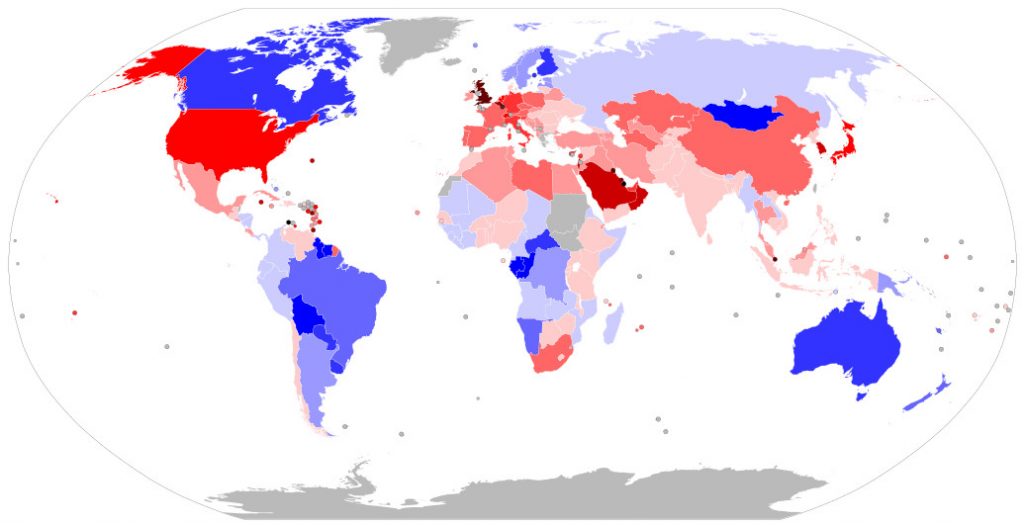

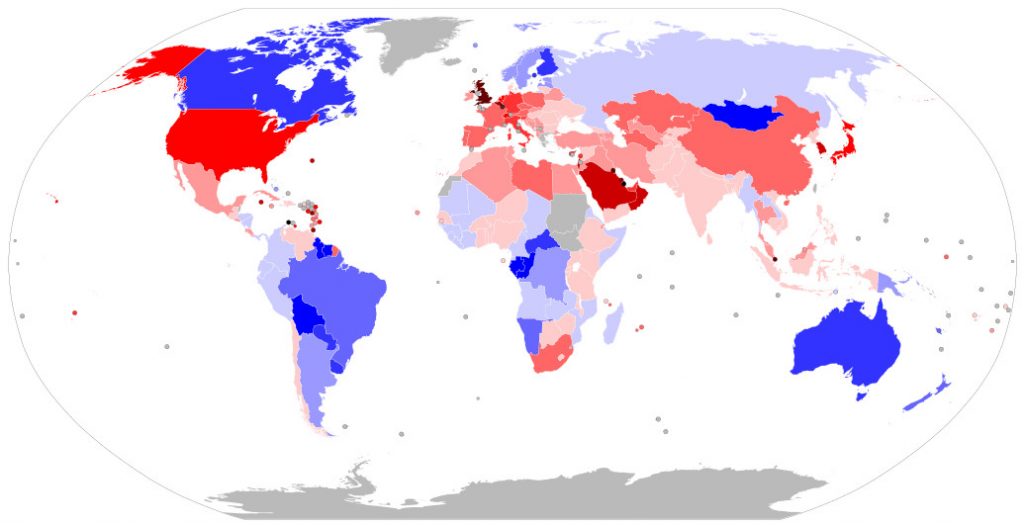

Ok, so the world is going to pieces and I feel I haven’t been helping much in the past years. Of course, I’m not alone. Statistically speaking, as you can see from the figure below, Europeans have a heavy ecological footprint, and it looks like Switzerland is no exception.

![]()

Ecological footprint by country: This figure shows the national ecological surplus (or deficit), measured as a country’s biocapacity per person minus its ecological footprint per person in 2013.

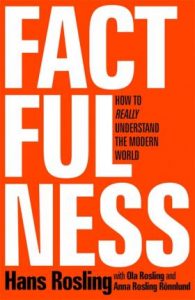

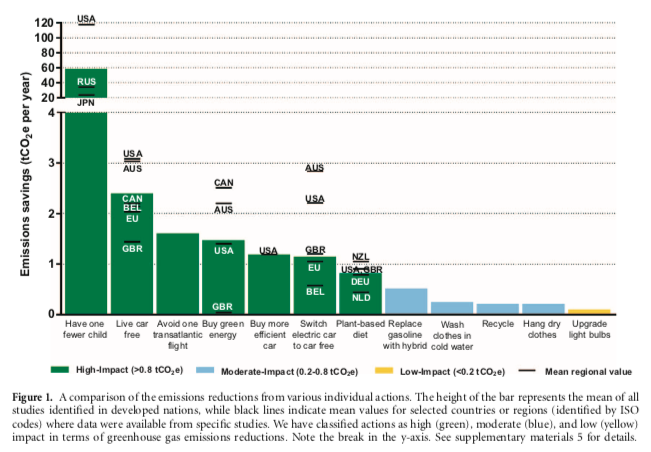

But what can I personally do about this? Short of dying, having fewer children could be the best way to reduce carbon emissions (see Figure below; Wynes & Nicholas, 2017), but, for me personally, deciding to not have more children doesn’t seem like much – I’m already the father of two and wasn’t planning on having more. I also don’t own a car and I’m a flexitarian…

Flying

Then there’s flying. Flying accounts for “only” about 2% of global carbon emissions but it is one of the few things I feel I can control as an individual. I have flown quite a bit for personal and professional reasons. I may also have contributed to other people’s flying by inviting researchers to visit Basel for talks/workshops and encouraging co-workers to attend conferences (“You’ve got to get yourself out there!”). Also, for most of these, I did not atone by offsetting associated carbon emissions. My sins have caught up with me – I’m experiencing a bad case of “flight shame”.

My Personal Fight Against Flight Shame

The problem is that there is a clear trade-off between the ecological costs of flying and professional development. Attending conferences and workshops is an important way to stay up to date on latest scientific developments and build (or keep) a network of collaborators – and science is more and more a collaborative enterprise.

After considerable soul-searching, I have come up with some personal rules to help me navigate this trade-off and accept a life in which flying is an exception:

- Think before booking. I now check the footprint of my travel using sites like ecopassanger. This may not seem like much but it now allows me to engage in an internal soliloquy pitting scientific/personal benefits agains ecological costs (in CO2 tonnes).

- Cut down on conferences. I’ve cut down on the number of conferences and workshops I attend, in particular those that would require intercontinental flights. This is sometimes tough. For example, I was recently invited to present at a a workshop that was a perfect fit for my research profile but would imply flying (involving over 4 tones CO2 emissions); unfortunately, the event would take place during the semester so I had trouble combining this trip with other scientific events or personal visits that would make me feel comfortable with the benefits/ecological-footprint ratio. Even though I ended up saying no, I wavered quite a bit, going back on forth on pros and cons (quantifying the ecological costs was helpful though).

- Taking the train. I’ve switched to taking trains for trips that I used to fly (e.g., Basel-Berlin) or, for long trips, doing 1-trip by train and then flying back (e.g., Basel-Lisbon).

- Carbon offsetting. When I do fly, I offset using sites like myclimate or atmosfair.

- Meeting remotely. I have a few international collaborations that I kindle using technology (e.g., Skype). It does not eliminate the need for personal interaction but it substitutes some meetings and can be used to help planning and increase productivity when one does end up meeting face-to-face. In our lab, we also have some good experience doing cross-lab collaboration using software, like covidence, which allows to have researchers (coders for meta-analysis) in two sites that interact remotely through the covidence software and Skype meetings.

- Letting the world come to me. I try to make the most of guests at our faculty (SWE Colloquium), other faculties at the University of Basel (such as the Faculty of Economics), and other meetings in Switzerland.

- Raise awareness. I’m trying to raise awareness by discussing this issue in our department (for example, by writing this blog post), and developing some guidelines concerning flying in our center (stay tuned, CDSers!).

- Thing globally, act locally. Finally, I have realised I need to get more active at a local level, supporting regional scientific networks and societies, making sure that we can do the best science right here at home.

I’m no trailblazer: This is a conversation that many want to have in science, as attested by recent papers in Nature, movements at German Universities, and some institutional programs at Swiss institutions, like the ETH. Of course, my personal set of rules and such trends may not be enough to save the world but #flyingless surely can’t hurt.

Wynes, S., & Nicholas, K. A. (2017). The climate mitigation gap: education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions. Environmental Research Letters, 12(7), 074024–10. http://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa7541