Anika Josef, David Richter, Greg Samanez-Larkin, Gert Wagner, Ralph Hertwig, and I have a new paper out on risk taking (abstract below). We were particularly interested in understanding how risk taking changes across the life span and whether it does so differentially across different domains, such as in driving, finance, or health domains. We were able to analyse data from a large longitudinal panel representative of the German population and estimate how much risk-taking propensity changes across intervals of up to 10 years in adults of 18 to 85 years of age!

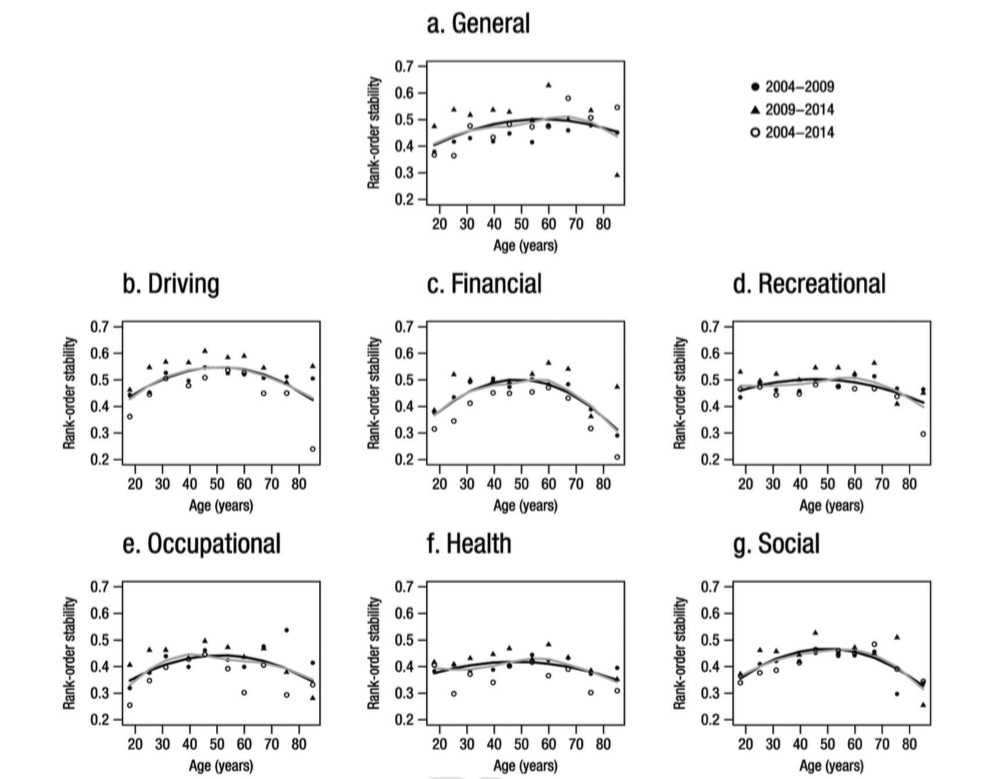

The results are quite interesting in suggesting that risk-taking propensity shows patterns of stability/change similar to those of other personality traits. For example, in the figure below, one can see an inverted U-shape pattern in test-retest stability (i.e., the correlation between two measurements that took place 5 or 10 years apart) across different life domains that matches what we know about other measures of personality such as the Big Five. The inverted-U shape indicates that there are periods in life, young adulthood and old age, when we are most likely to change our risk-taking propensity. One question raised by these results and that we hope to address in the future is what are the specific life events that lead to such changes…

Stability and Change in Risk-Taking Propensity Across the Adult Life Span

Can risk-taking propensity be thought of as a trait that captures individual differences across domains, measures, and time? Studying stability in risk-taking propensities across the life span can help to answer such questions by uncovering parallel, or divergent, trajectories across domains and measures. We contribute to this effort by using data from respondents aged 18 to 85 in the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) and by examining (a) differential stability, (b) mean-level differences, and (c) individual-level changes in self-reported general (N = 44,076) and domain-specific (N = 11,903) risk-taking propensities across adulthood. In addition, we investigate (d) the correspondence between cross-sectional trajectories of self-report and behavioral measures of social (trust game; N = 646) and nonsocial (monetary gamble; N = 433) risk taking. The results suggest that risk-taking propensity can be understood as a trait with moderate stability. Results show reliable mean-level differences across the life span, with risk-taking propensities typically decreasing with age, although significant variation emerges across domains and individuals. Interestingly, the mean-level trajectory for behavioral measures of social and nonsocial risk taking was similar to those obtained from self-reported risk, despite small correlations between task behavior and self-reports. Individual-level analyses suggest a link between changes in risk-taking propensities both across domains and in relation to changes in some of the Big Five personality traits. Overall, these results raise important questions concerning the role of common processes or events that shape the life span development of risk-taking across domains as well as other major personality facets.

Josef, A. K., Richter, D., Samanez-Larkin, G. R., Wagner, G. G., Hertwig, R., Mata, R. (2016). Stability and change in risk-taking propensity across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000090