Three identical strangers is a sobering documentary about triplets raised apart that were part of an unethical study.

The movie does a great job of portraying the drama involved in the reunion of three brothers and their relationship from their late teens (19) onwards when two of them met by chance (the third learned about the 2 brothers through a newspaper article about their reunion). Importantly, the movie details how the three brothers learned about their role as study subjects and their difficulties in finding out about the study goals and what information was collected about them across their childhood and adolescence.

The study seems to have been the product of an agreement between a psychiatrist and an adoption agency to develop a longitudinal study of twins reared apart in which the children were placed in specific types of family (e.g., different types of socio-economic background) and which the host families (and twins) were unwittingly part of. The documentary makes a lot out of the results of the study never having been published. Yet, the study seems to have involved only a few twins (numbers of ca. 8 are mentioned in the movie, the wikipedia entry mentions 13 pairs) so it is unlikely that it would represent a strong contribution to the literature. Further, and most likely, the backlash felt from the families discovering the unethical character of the study led the involved scientists to avoid further polemic by not publishing any of it.

I liked the documentary but found it unfortunate that it sketches a picture of twin studies as rather inconclusive and ends on a number of general intuitions about the importance of nurture to individuals’ personalities (along the lines of the importance of parenting). It is rather odd that a documentary that explicitly aims to get us to think about the nature-nurture debate, and focuses on “uncovering” a twin study, fails to invite experts in this field to discuss such ethical issues and give a more informed view of the science accumulated over the past decades.

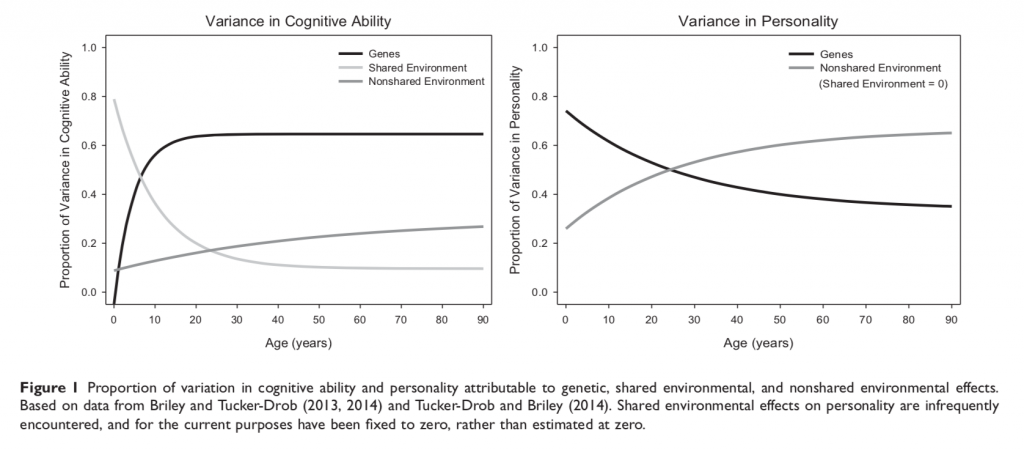

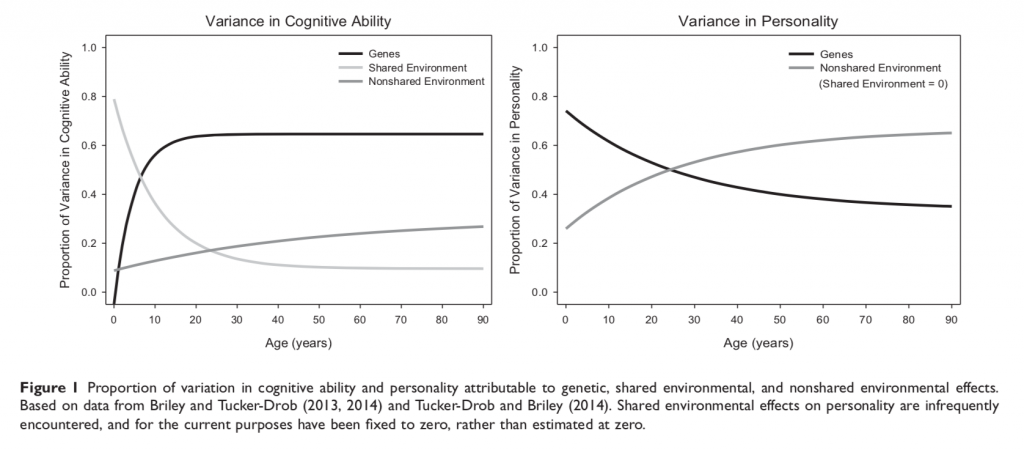

In fact, from the over 2700 publications on over 14.5 million twins that have been produced, we have learned a lot about the influence of hereditary factors on many human traits, including psychological ones (Polderman et al., 2015). Contradicting some of the intuitions expressed in the documentary, there is an important role of genetics (“nature”) in both intelligence and personality (with the heritability of intelligence higher relative to intelligence, ca. .6 vs. .4 at adult ages; see below Figure 1 from Briley & Tucker-Drop, 2015).

Crucially, as can be seen in the panel on the right, the influence of shared environment – those influences that are shared among twins, such as parenting – on personality is low, indeed, 0 (according to Briley & Tucker-Drop, 2015), with the remaining variance being explained by non-shared environment – the product of the unique physical and social experiences that result from interactions with peers, friends, and partners over the course of our lives.

Perhaps this knowledge could have better helped the twins put in perspective the role played by the study in shaping their lives.

Briley, D. A., & Tucker-Drob, E. M. (2015). Comparing the developmental genetics of cognition and personality over the life span. Journal of Personality, 85(1), 51–64. http://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12186

Polderman, T. J. C., Benyamin, B., de Leeuw, C. A., Sullivan, P. F., van Bochoven, A., Visscher, P. M., & Posthuma, D. (2015). Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nature Genetics, 47(7), 702–709. http://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3285