Archive for the ‘future’ Category

IMPULS

Want to make the world a better place by integrating the Sustainable Development Goals into your teaching or mentoring? Consider getting financial support or domain-specific training through the IMPULS program offered by the Sustainability Office of the University of Basel!

career planning

Our student organization, FG Psychologie Basel, and the Career Service Center of our university are organizing a career workshop for psychology students this semester, that will take place

October 15, 2020, 16:15-17:45, via Zoom

Find the flyer (including a Zoom link) here.

sustainability

There is a new working group at the University of Basel that aims to get students and staff to contribute to making our university more sustainable – AG Nachhaltigkeit. The idea is to complement the top-down work of the Sustainability office with some grassroots activism. For example, the kickoff meeting in January involved brainstorming about ideas to make our university more sustainable that spanned from reducing plastic waste in science labs to making Ecosia the search engine of choice.

The next planned meeting will take place February 27, 2020, (Rm 035 Kollegienhaus) and will include an overview of ongoing work by the Sustainability office of the University of Basel – including some projects that have struggled (or failed) in the past and others that could use further help from students and staff.

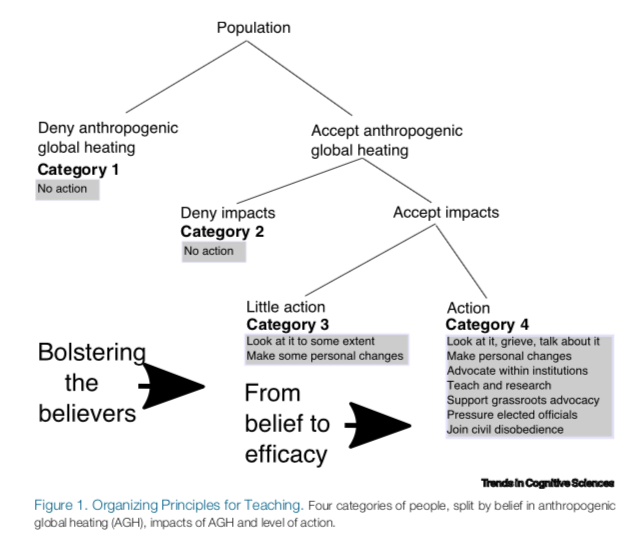

There is much to be said about psychologists and other social scientists being engaged in such initiatives (e.g., Aron, 2019). After all, we should be well equipped (or willing to learn!) to use data science to assess beliefs and behaviour, deploy theory to design persuasive communication campaigns, and capitalise on techniques that can help others change their habits.

We are the weather

I read “We are the weather” by Jonathan Safran Foer over the weekend and found it quite stimulating. Foer intertwines science with historical anecdotes and personal history to make for an engaging read.

The book is an ecological manifesto for reducing the consumption of animal products. The main premise is that the world has become an animal farm, with animal husbandry being one of the major contributors to man-made climate change, something between 14% to 51% of CO2e emissions (the epistemic uncertainty about this estimate is discussed in the book’s appendix).

Foer’s proposal is to forgo meat and dairy before dinner. This seems like a half-measure given the strong case against animal farming that Foer makes earlier in the book – an attempt to spare sensibilities of meat-eaters and flexitarians around the world (after all they buy books too!). Also, surprinsigly, Foer does little to discuss other measures of climate change mitigation, such as transportation (driving or flying) that are also well in the realm of behaviours that individuals can control.

I find the book is at its strongest not in it’s proposal regarding the consumption of animal products but how Foer discusses the personal struggle of changing one’s own behaviour to match one’s beliefs. For example, Foer describes how he’s failed to adopt a vegan life-style despite his convictions, and how he sometimes has trouble resisting the forbidden burger at the airport, or the enticing dairy at breakfast. After learning everything there is to learn about climate change one can still fail to act in accordance with one’s best knowledge.

The Science of Behaviour Change

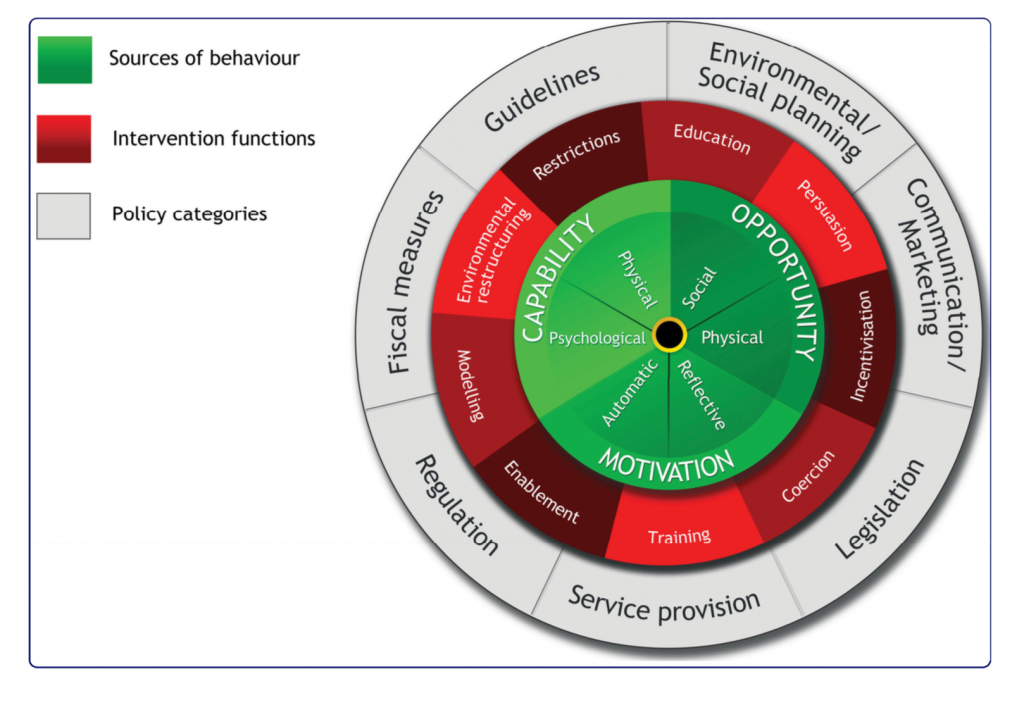

Psychology is of course a science of behaviour change and it has much to help in guiding both individuals and institutions in this regard. Importantly, our field is moving away from single hyped-up panaceas (e.g., nudges) to more encompassing theories that include changes of the physical and social environment, as well as cognitive and motivational processes. Susan Michie has done a lot to put this work on a solid footing by creating a taxonomy of behaviour change techniques and an empirical agenda to assess their efficacy (you can find an introduction to Michie et al.’s behaviour change wheel in Michie, van Stralen, & West, 2011).

This work stems from the field of health psychology, concerned with issues like obesity, physical activity, and smoking, and so its straightforward to apply it to the nutrition choices that Foer discusses. One can also see how similar principles can be translated into other life style changes, such as transportation choices.

The science is in and we’ve got the tools – it’s time for psychologists to suit up for: “Behaviour change, not climate change!”

flying less

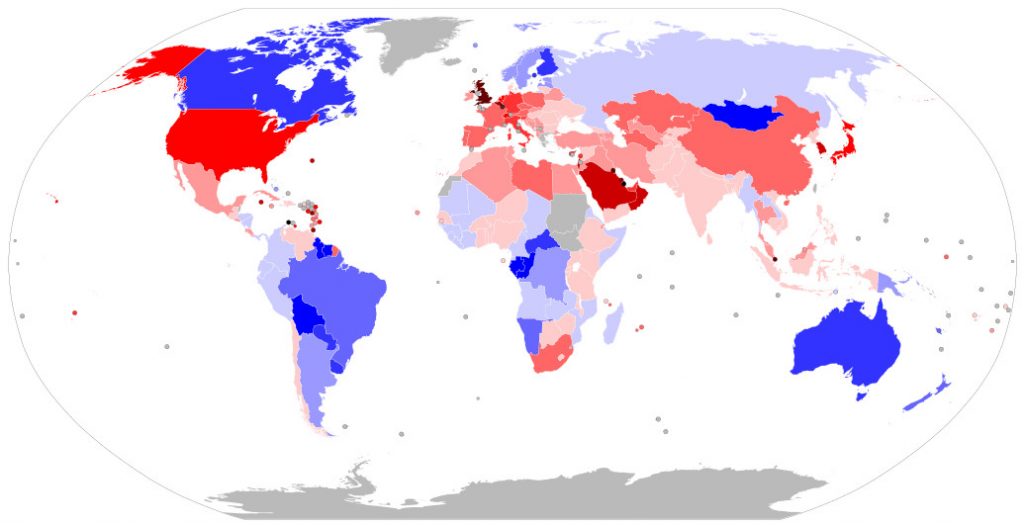

Ok, so the world is going to pieces and I feel I haven’t been helping much in the past years. Of course, I’m not alone. Statistically speaking, as you can see from the figure below, Europeans have a heavy ecological footprint, and it looks like Switzerland is no exception.

Ecological footprint by country: This figure shows the national ecological surplus (or deficit), measured as a country’s biocapacity per person minus its ecological footprint per person in 2013.

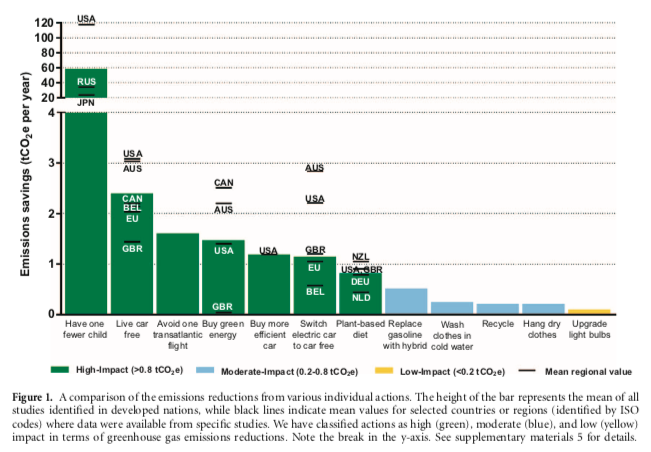

But what can I personally do about this? Short of dying, having fewer children could be the best way to reduce carbon emissions (see Figure below; Wynes & Nicholas, 2017), but, for me personally, deciding to not have more children doesn’t seem like much – I’m already the father of two and wasn’t planning on having more. I also don’t own a car and I’m a flexitarian…

Flying

Then there’s flying. Flying accounts for “only” about 2% of global carbon emissions but it is one of the few things I feel I can control as an individual. I have flown quite a bit for personal and professional reasons. I may also have contributed to other people’s flying by inviting researchers to visit Basel for talks/workshops and encouraging co-workers to attend conferences (“You’ve got to get yourself out there!”). Also, for most of these, I did not atone by offsetting associated carbon emissions. My sins have caught up with me – I’m experiencing a bad case of “flight shame”.

My Personal Fight Against Flight Shame

The problem is that there is a clear trade-off between the ecological costs of flying and professional development. Attending conferences and workshops is an important way to stay up to date on latest scientific developments and build (or keep) a network of collaborators – and science is more and more a collaborative enterprise.

After considerable soul-searching, I have come up with some personal rules to help me navigate this trade-off and accept a life in which flying is an exception:

- Think before booking. I now check the footprint of my travel using sites like ecopassanger. This may not seem like much but it now allows me to engage in an internal soliloquy pitting scientific/personal benefits agains ecological costs (in CO2 tonnes).

- Cut down on conferences. I’ve cut down on the number of conferences and workshops I attend, in particular those that would require intercontinental flights. This is sometimes tough. For example, I was recently invited to present at a a workshop that was a perfect fit for my research profile but would imply flying (involving over 4 tones CO2 emissions); unfortunately, the event would take place during the semester so I had trouble combining this trip with other scientific events or personal visits that would make me feel comfortable with the benefits/ecological-footprint ratio. Even though I ended up saying no, I wavered quite a bit, going back on forth on pros and cons (quantifying the ecological costs was helpful though).

- Taking the train. I’ve switched to taking trains for trips that I used to fly (e.g., Basel-Berlin) or, for long trips, doing 1-trip by train and then flying back (e.g., Basel-Lisbon).

- Carbon offsetting. When I do fly, I offset using sites like myclimate or atmosfair.

- Meeting remotely. I have a few international collaborations that I kindle using technology (e.g., Skype). It does not eliminate the need for personal interaction but it substitutes some meetings and can be used to help planning and increase productivity when one does end up meeting face-to-face. In our lab, we also have some good experience doing cross-lab collaboration using software, like covidence, which allows to have researchers (coders for meta-analysis) in two sites that interact remotely through the covidence software and Skype meetings.

- Letting the world come to me. I try to make the most of guests at our faculty (SWE Colloquium), other faculties at the University of Basel (such as the Faculty of Economics), and other meetings in Switzerland.

- Raise awareness. I’m trying to raise awareness by discussing this issue in our department (for example, by writing this blog post), and developing some guidelines concerning flying in our center (stay tuned, CDSers!).

- Thing globally, act locally. Finally, I have realised I need to get more active at a local level, supporting regional scientific networks and societies, making sure that we can do the best science right here at home.

I’m no trailblazer: This is a conversation that many want to have in science, as attested by recent papers in Nature, movements at German Universities, and some institutional programs at Swiss institutions, like the ETH. Of course, my personal set of rules and such trends may not be enough to save the world but #flyingless surely can’t hurt.

scientists for future

Gemeinsame Stellungnahme deutscher, österreichischer

und Schweizer Wissenschaftlerinnen und Wissenschaftler

zu den Protesten für mehr Klimaschutz.