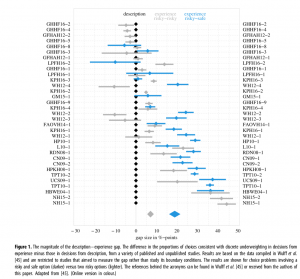

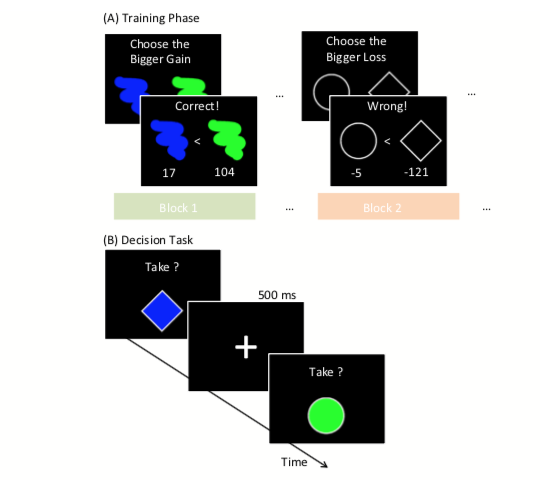

Sebastian Horn, Thorsten Pachur, and I have a new paper out comparing children and young adults on value-based decisions from memory. We adapted a neat paradigm (see above for a rough depiction) that allows a good control of the information to be compared in memory and can give some insight in to potential differences between children of different ages and adults’ decisions requiring the comparison of gains and losses from memory. Our results suggest that children were somewhat less efficient in making such decisions due to developmental differences in both memory and aritmethic abilities. We believe this work illustrates how it is possible to assess the contribution of different core abilities (such as memory or arithmetic skill) to individual and age differences in decision making. The abstract and full reference are given below.

Good + Bad = ? Developmental Differences in Balancing Gains and Losses in Value‐Based Decisions From Memory

Value‐based decisions often involve comparisons between benefits and costs that must be retrieved from memory. To investigate the development of value‐based decisions, 9‐ to 10‐year olds (N = 30), 11‐ to 12‐year olds (N = 30), and young adults (N = 30) first learned to associate gain and loss magnitudes with symbols. In a subsequent decision task, participants rapidly evaluated objects that consisted of combinations of these symbols. All age groups achieved high decision performance and were sensitive to gain–loss magnitudes, suggesting that required core cognitive abilities are developed early. A cognitive‐modeling analysis of performance revealed that children were less efficient in object evaluation (drift rate) and had longer nondecision times than adults. Developmental differences, which emerged particularly for objects of high positive net value, were linked to mnemonic and numerical abilities.