Perhaps you remember a previous blog post in which we (Laura Fontanesi and Loreen Tisdall) announced an exciting research collaboration we were part of: the Neuroimaging Analysis Replication and Prediction Study (NARPS). Fast forward 18 months, and we are happy to announce that the resultant paper (Botvinik-Nezer et al., 2020, Nature) is now published, you can read it here. Below, we share a summary of the study, the results, and our thoughts on what to make of it all.

Inside NARPS

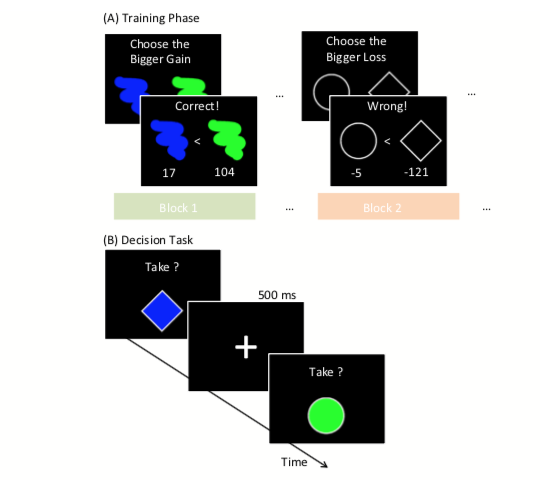

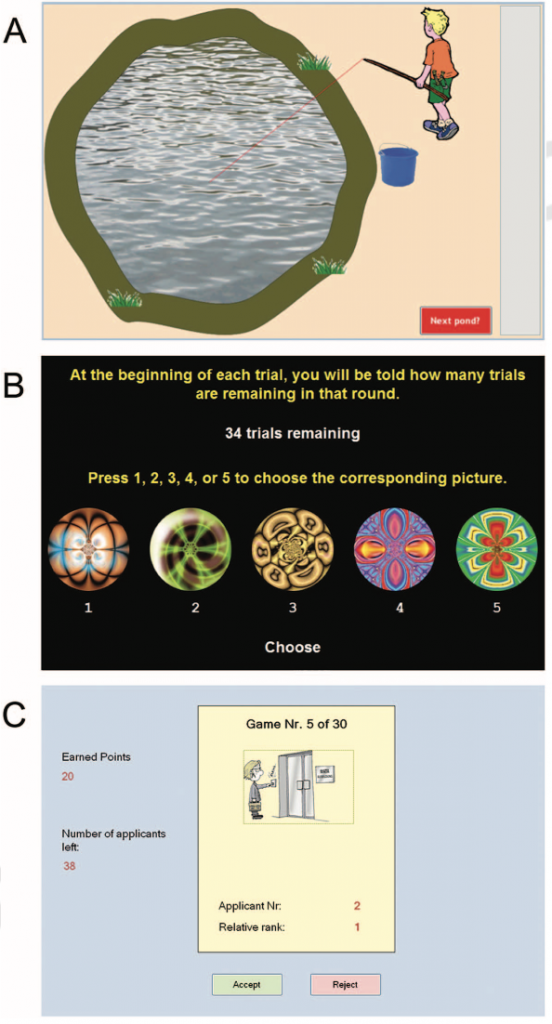

Our adventure with NARPS started at the meeting of the Society for NeuroEconomics in Philadelphia in October 2018. That’s where we met Tom Schonberg, busy with recruiting analysis teams for the project. The main idea of NARPS’ leading researchers was to collect a somewhat large (n > 100) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) dataset, provide this data to many teams across the world, and ask them to independently test nine predefined hypotheses. The task chosen for this endeavor was a mixed-gambles task, which is widely used for studying decision-making under risk. Crucially, the motivation behind the project was not to find the truth about value-related signals in the human brain. Instead, the goal was to estimate the agreement across independent research teams on hypothesis testing based on fMRI data, when little to no instructions are provided on the methods or software to be used. On top of that, the project leaders were planning to let a second group of researchers bet on the results of such agreement, before the results were out. In light of the replication crisis in psychology and to a lesser extent also in economics, a study on the reliability of empirical findings in neuroeconomics seemed almost due at that point. Plus, this study reminded us of a similar many-analysts project in the cognitive modeling field, where independent teams were asked to use a cognitive model to test behavioral effects of experimental manipulations, and found that conclusions were affected by the specific software they used.

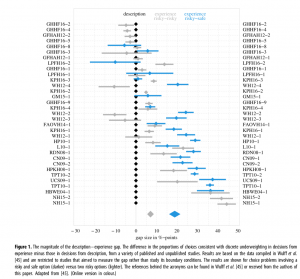

The most crucial result coming from NARPS is that the agreement on null hypothesis rejection was overall quite low. On average, across the nine hypotheses, 20% of the teams reported a different result from the majority of the teams. Crucially, maximum disagreement between teams is marked by 50% (i.e., 50% of teams report results which support, and 50% of teams report results which reject a given hypothesis). Given this benchmark, a 20% disagreement rating is almost ‘halfway’ between maximum agreement and maximum disagreement. Surprisingly, the probability to find a significant result was not affected by the choice of using preprocessed data, and the statistical brain activation maps (before thresholding) were highly correlated across the teams. Therefore, the statistical decisions that are made in later stages of fMRI analyses (e.g., how to correct for multiple corrections) might actually play the most crucial role in null hypothesis testing. In addition, the prediction market revealed an “optimism bias”: Researchers (including a subset of researchers who had participated in the data analysis part of NARPS) overestimated the probability of finding significant results.

Beyond NARPS

The title of the NARPS publication is ‘Variability in the analysis of a single neuroimaging dataset by many teams’. Importantly, variability in analytical pipelines is not a problem, per se. In fact, we often engage with the analytical multiverse that surrounds every single piece of research (simply because there are always varying ways of examining research questions and testing hypotheses) and check the sensitivity of our results to analytical variability. However, the NARPS findings suggest that the use of different analytical pipelines can produce results which support opposite conclusions. In the spirit of replicability, this is not a desired outcome.

So, what now? Should we scrap all neuroimaging research? In our opinion, the NARPS findings highlight two important issues: (1) open science is the way to go, and (2) more many-analysts projects are needed to understand how widespread this problem is across tasks, brain regions, and/or neuroimaging techniques.

First, let’s start with the main take-home message of the paper: Considering that analytical decisions can have a big impact on research findings and conclusions, it is of crucial importance to thoroughly plan and clearly communicate analytical pipelines. In other words, go full throttle on transparency and open science: Preregister your study, apply optimized preprocessing pipelines, consider the suitability of your smoothing kernel given your anatomical regions of interest, be transparent about significance thresholds, share your code and data, and share your unthresholded activation maps.

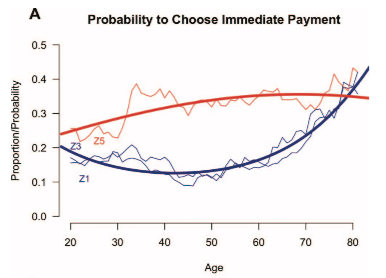

Second, we think it is also important to consider the generalizability of the NARPS findings. In particular, we noticed that the choice of the behavioral task was not part of the public discourse (see here and here for examples) triggered by the NARPS publication. In our opinion, individual differences play an important role in the mixed-gambles task, both at the behavioral (risk preferences) and the neural level, and such variability can lead to lower statistical power (especially when spatial smoothing is not optimal for a given anatomical region). On top of that, response times (RTs) in this task are difficult to dissociate from the signal of interest, because RTs are highly correlated with option values. In fact, this could cause power issues that might not be relevant for other neuroeconomics tasks, or tasks in different psychological domains.

To understand the role of the task and, importantly, the extent to which the NARPS findings generalize to the entire field of neuroimaging, ideally we would use the NARPS approach to study variability in results observed for (1) other decision-making tasks, (2) other fields, such as visual perception, (3) off-task functional activation differences (resting state), (4) other imaging modalities (e.g., EEG, MEG, eye tracking), and (5) other methodological approaches (e.g., model-based cognitive neuroscience). When polled on Twitter, 64.6% of M/EEG researchers (N=601) indicated that a similar approach in their field would lead to results that are more consistent than the results found for fMRI; the jury is out on whether this response pattern mirrors the overconfidence reported for fMRI results.

In summary, we thoroughly enjoyed being part of NARPS. This project was not only timely, but revealed that we might be overly optimistic about the reliability of fMRI analyses. It also revealed that our statistical decisions in the analysis pipeline (e.g., how to correct for multiple comparisons) make substantial contributions to this lack of reliability (as opposed to decisions during data preprocessing). Our hope is that NARPS will motivate more many-analyst projects in different neuroimaging subfields and methodologies.