I read “We are the weather” by Jonathan Safran Foer over the weekend and found it quite stimulating. Foer intertwines science with historical anecdotes and personal history to make for an engaging read.

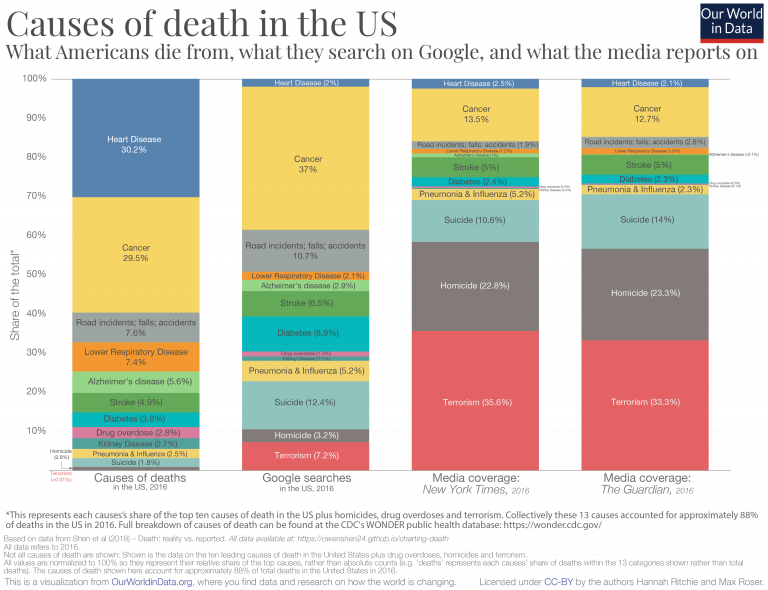

The book is an ecological manifesto for reducing the consumption of animal products. The main premise is that the world has become an animal farm, with animal husbandry being one of the major contributors to man-made climate change, something between 14% to 51% of CO2e emissions (the epistemic uncertainty about this estimate is discussed in the book’s appendix).

Foer’s proposal is to forgo meat and dairy before dinner. This seems like a half-measure given the strong case against animal farming that Foer makes earlier in the book – an attempt to spare sensibilities of meat-eaters and flexitarians around the world (after all they buy books too!). Also, surprinsigly, Foer does little to discuss other measures of climate change mitigation, such as transportation (driving or flying) that are also well in the realm of behaviours that individuals can control.

I find the book is at its strongest not in it’s proposal regarding the consumption of animal products but how Foer discusses the personal struggle of changing one’s own behaviour to match one’s beliefs. For example, Foer describes how he’s failed to adopt a vegan life-style despite his convictions, and how he sometimes has trouble resisting the forbidden burger at the airport, or the enticing dairy at breakfast. After learning everything there is to learn about climate change one can still fail to act in accordance with one’s best knowledge.

The Science of Behaviour Change

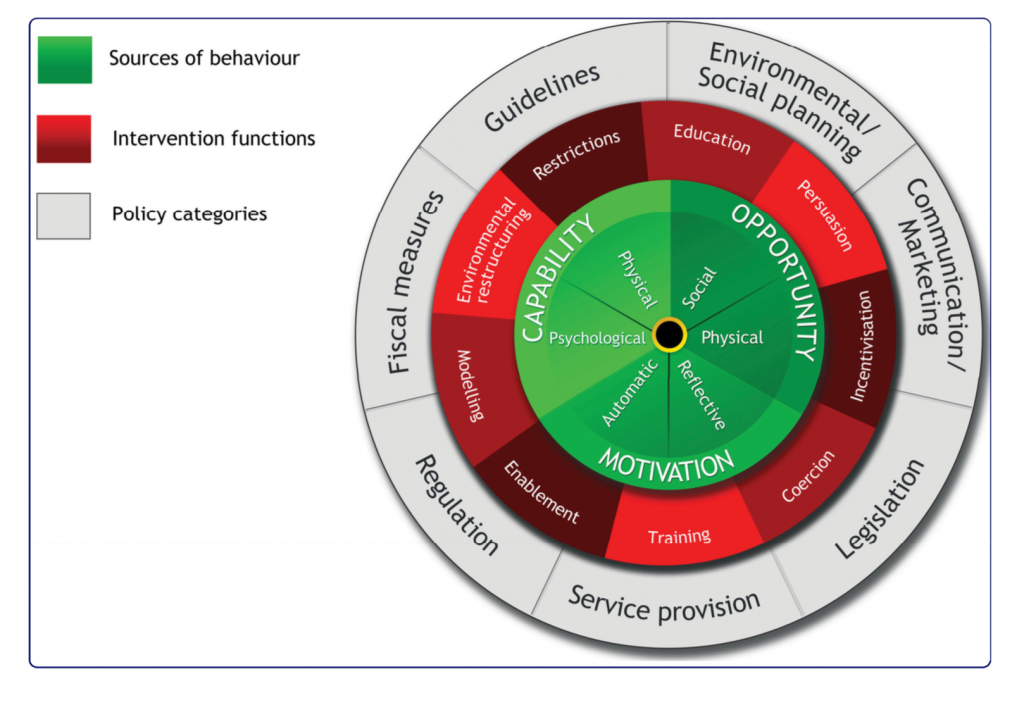

Psychology is of course a science of behaviour change and it has much to help in guiding both individuals and institutions in this regard. Importantly, our field is moving away from single hyped-up panaceas (e.g., nudges) to more encompassing theories that include changes of the physical and social environment, as well as cognitive and motivational processes. Susan Michie has done a lot to put this work on a solid footing by creating a taxonomy of behaviour change techniques and an empirical agenda to assess their efficacy (you can find an introduction to Michie et al.’s behaviour change wheel in Michie, van Stralen, & West, 2011).

This work stems from the field of health psychology, concerned with issues like obesity, physical activity, and smoking, and so its straightforward to apply it to the nutrition choices that Foer discusses. One can also see how similar principles can be translated into other life style changes, such as transportation choices.

The science is in and we’ve got the tools – it’s time for psychologists to suit up for: “Behaviour change, not climate change!”