I read Factfulness over the summer, the posthumously published book by Hans Rosling (coauthored with Anna Rosling Rönnlund and Ola Rosling). The book is an easy and entertaining read. You may know some of these authors’ work from their TED talks – and the book does justice to the message and entertainer quality of the Rosling team.

Factfulness is a strong manifesto for combating ignorance with data. The idea that evidence-based decisions are needed to improve living conditions around the world may seem a truism but the Roslings really bring the message home by, first, letting readers assess their own ignorance (readers are asked to do an initial quizz that is likely to make one feel rather ignorant about demographics, living conditions, and other aspects of life around the world). Second, the Roslings list “heuristics” that both experts and laypeople may use to make sense of the world from their rather limited knowledge (labelled Gap, Negativity, Straight Line, Fear, Size, Generalization, Destiny, Single, Blame, and Urgency) and that they suggest we must keep in check by considering (up to date) data. As a psychologist, one may wonder whether these “heuristics” are actually used or what the cognitive mechanisms underlying the discussed phenomena really are but, that aside, the 10-point program works to keep us engaged and figuring out how data (when visualized appropriately) can help correct false assumptions.

On this note, I recently found a worthy initiative that seems to embody the “factfulness” spirit: Our world in data. The initiative led by Max Roser, University of Oxford, is to use “research and data to make progress against the world’s largest problems”. Our World in Data publishes short online “articles”, each focusing on a specific topic and typically providing a mix of review and many visualisations of (mostly publicly available) data. One particularly interesting piece I read recently was “Does the news reflect what we die from?”

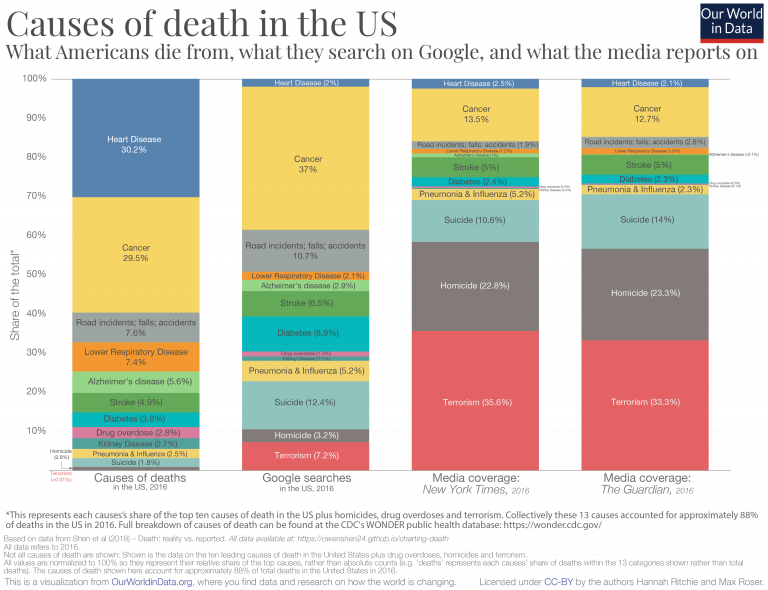

The piece reports analyses of the causes of deaths in the USA (from public records), Google search trends for causes of deaths, as well as mentions of causes of deaths in the New York Times and The Guardian. As you can see in the figure below, “the news doesn’t reflect what we die from” and this of course has implications for issues of risk perception and communication: If the public is given wrong (non-representative) information, can we expect public opinion to have adequate preferences for action concerning these causes of death?

Of course, knowledge isn’t everything. After all, many people know that smoking and sugary drinks are bad for one’s health but this does not keep many individuals from cigarettes and soda. Be that as it may, some more factfulness in our lives is probably a good thing and it’s good to see the social sciences make use of data to understand the world.

Be the first to leave a comment. Don’t be shy.