The 2016 US Presidential race is proving quite entertaining. One aspect that has not taken center stage is the Democratic and Republican candidates’ age. Yet, Hillary Clinton, 68, is the oldest Democratic nominee to date, while Trump, at 70, is the 4th oldest Republican nominee ever, begging the question of whether candidates’ age represents a relevant political factor. One reason why age could be a topic is voters’ concern that older individuals are not up to the demands of the presidential office. Another, less discussed, but potentially relevant issue, is whether candidates’ age has implications for their political decisions.

It’s worth mentioning that while presidential candidates have been getting older in the past decades, the relative age of US candidates relative to the mean life expectancy has stayed constant. In other words, candidates seem to be getting older in proportion to the average age of US citizens. Moreover, health concerns regarding a candidate can in principle be dispelled through some sort of vetting, such as it is (typically) done by making candidates’ health records public.

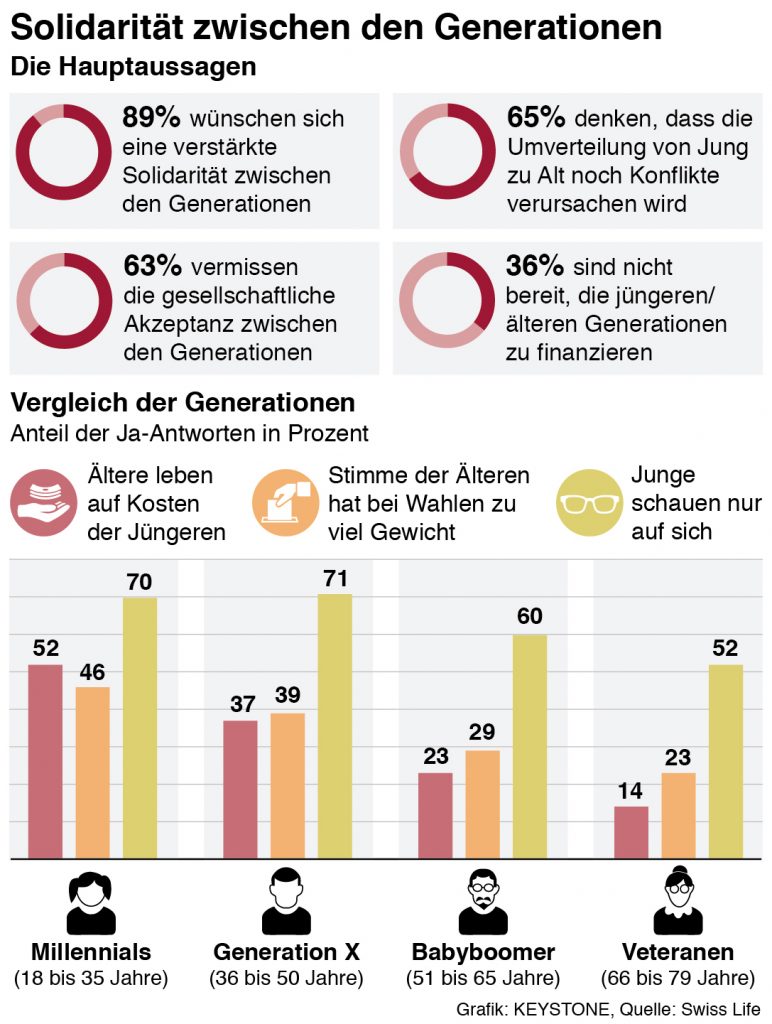

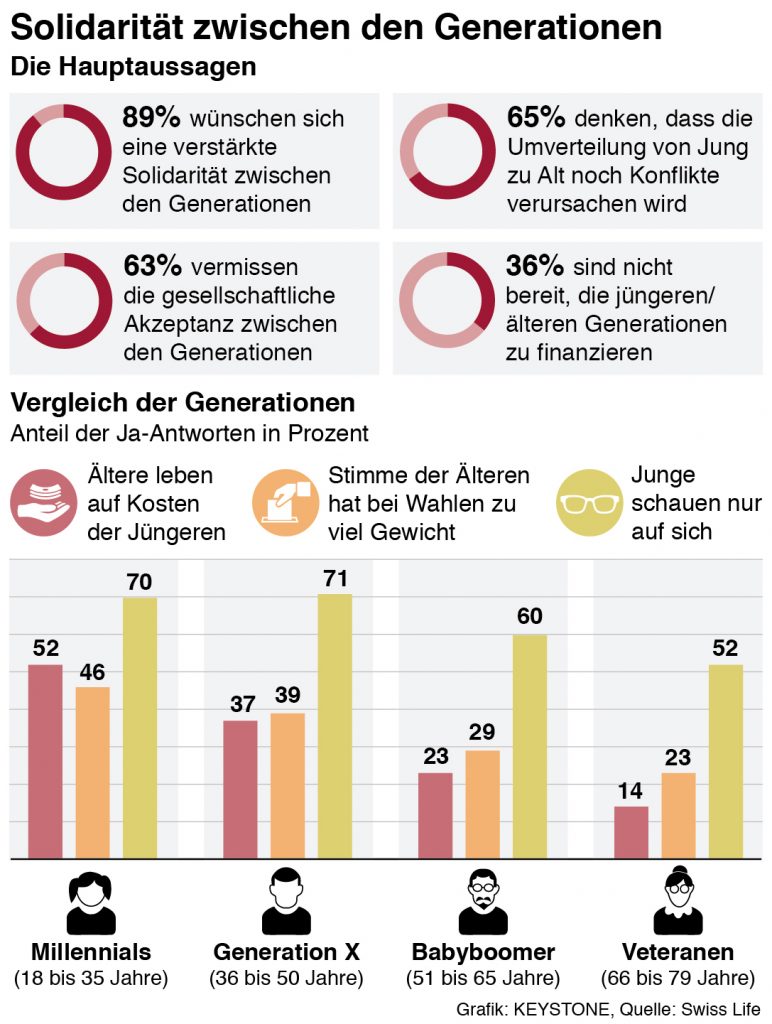

Understanding the political implications of an hegemony of older politicians is interesting – albeit hard to pin down. It is clear that younger and older voters have different opinions about policy, suggesting that this could be the case for politicians as well. For example, according to a recent poll in Switzerland, younger individuals feel that older adults live at their expense and may not have the same priorities (see the infographic below). Importantly, younger voters also seem to feel that older voters have too much weight concerning issues for which the main implications will take place in the distant future, such as those regarding the funding of social security.

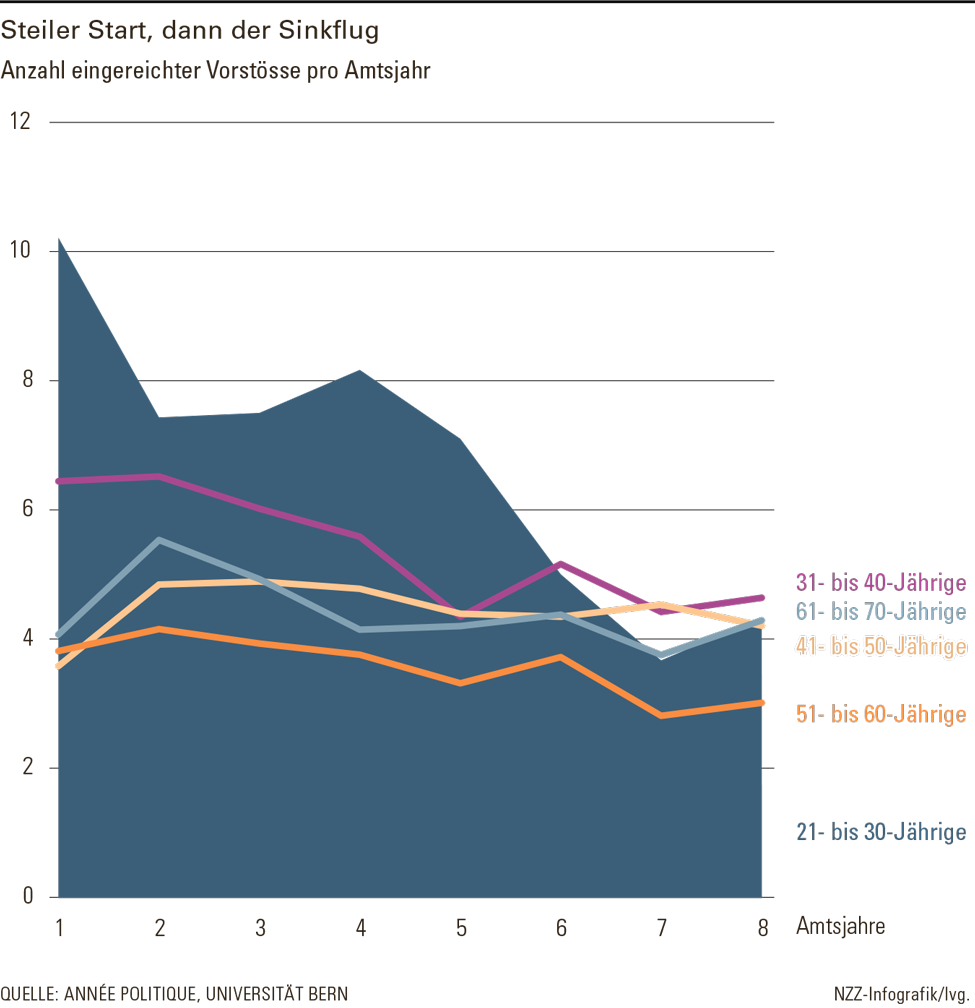

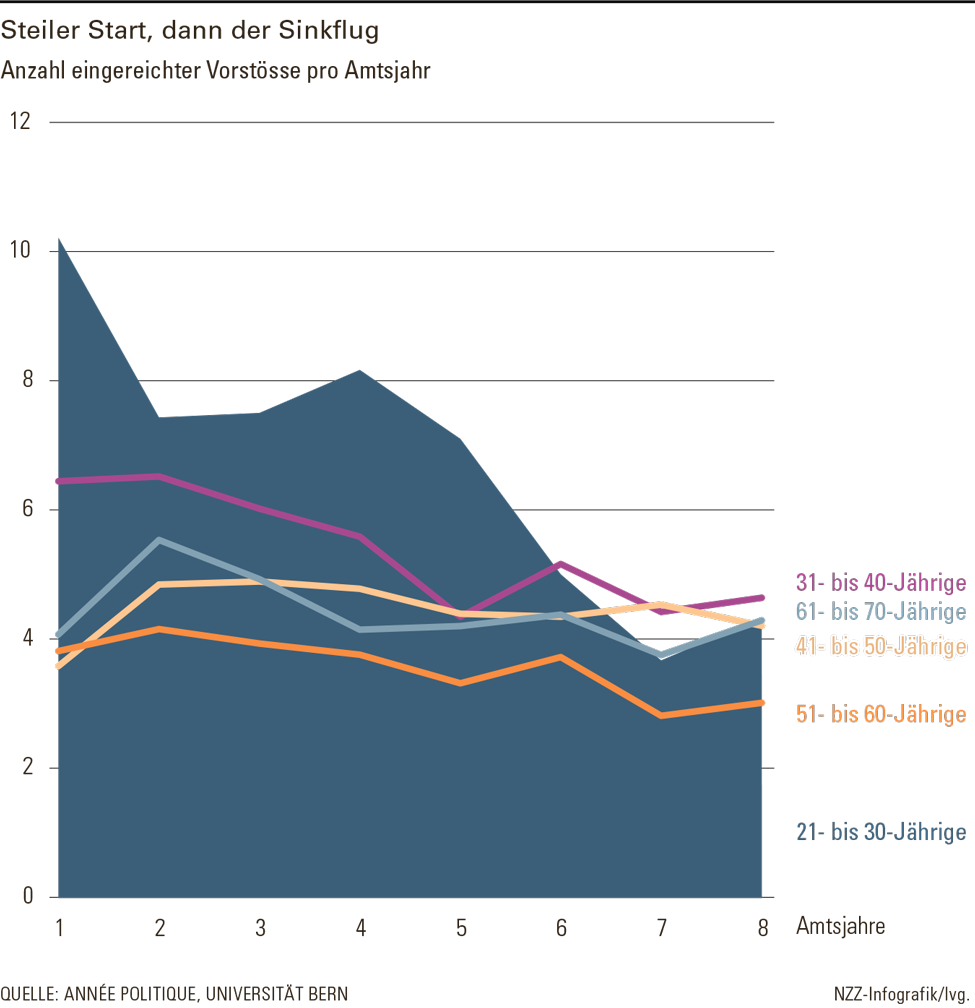

In addition, young and older politicians seem to have different strategies and approaches to policy making. For example, a recent study from Année Politique Suisse suggests that younger Swiss parliamentarians make a larger number of proposals but, over time, come in line with the (older) establishment, most likely as a function of experience with failed initiatives.

Of course, a political candidate isn’t only (or mostly) defined by his or her age, just like he or she isn’t simply defined by other single characteristics, like gender, religion, and so on. Regardless, in the current political scene in which so many decisions with long-term consequences must be made, including those concerning the acceptable amount of sovereign debt or the future of entitlements, politicians and voters’ age may become ever more relevant.